This is the blog post I wrote for my entry for the Art4Agriculture Young Farming Champions program. It covers why I am so proud to be apart of the Australian Agricultural Industry and why I think it has such a fantastic future...

In the late 1600’s, John Grills and his wife Urah, moved to St. Mellion, Cornwell England, where John practiced the trade of a worsted-comber 1. Four generations later, John (IV) and his wife Rebecca, decided to emigrate to Australia, settling in Maitland, NSW where John was a soldier, stonecutter and farmer. Their son Thomas, moved to Saumarez, Armidale where he married Ellen O’Connor and selected land on the eastern fall country of the New England Tablelands in 1881. Thomas and Ellen had 11 children, who went on to have 73 grandchildren, many of whom remained on the land. This property, along with later purchases, remains in the family to this day.

Agriculture was also very prominent in my mothers’ side of the family. In 1833, in Langport, Somersetshire England, John Turner married his wife Sophia. Four children later, they decided to make the journey to Australia in 1849. Initially settling in Adelaide they followed the Gold Rush to Victoria where they settled in Adelong in 1860. Here, John invented the first known steam crushing mill for gold. They also erected a school and were well respected in the area. The family continued the Agricultural tradition and bred cattle and sheep, as well as operating a dairy, wine and chaff making industries. One of their sons, Octavius (Doc), moved to the New England area which is where my mums’ family have remained.

After selecting the original country in 1881, a further two blocks of land were purchased over the next 40 years by Thomas and Ellen. Ellen went on to leave this land to the women of her family, until her three grandsons took it over as a partnership in 1960. The partnership was dissolved towards the end of the decade, and country was split into three separate properties. My father has gone to great lengths over his lifetime, to get back all of this country to once again make it one, and this is where I had the privilege of growing up as a seventh generation Aussie farmer. You would be quite right to say ‘it’s in my blood’.

The start of a family farm …

My grandfather took on the mammoth task of changing his block into a productive property. The 2200 ha were split into just 5 paddocks at the time, the soil had never seen superphosphate, bare ground was prominent under the heavily timbered country and rabbits were a constant problem. He set about developing the land by ringbarking trees, aerial seeding the country and also spreading super phosphate by plane.

My Grandfather standing amongst the ringbarked trees

The country was first improved on the ground with two TE 20 Ferguson tractors, pulling 7ft gear to put down introduced grasses to improve the productivity of the country in 1954. In 1959, the country benefited from the first aerial fly out of super phosphate in bagged form, which was hand lifted into the plane in 50kg bags. The ground application of super was also put out with the improved pasture seed. In 1972, the first woolshed was built on the northern end of the property. Prior to this, sheep would need to be walked anywhere up to 15 km to the other end of the original property, which my uncle then owned following the partnership being dissolved in 1967.

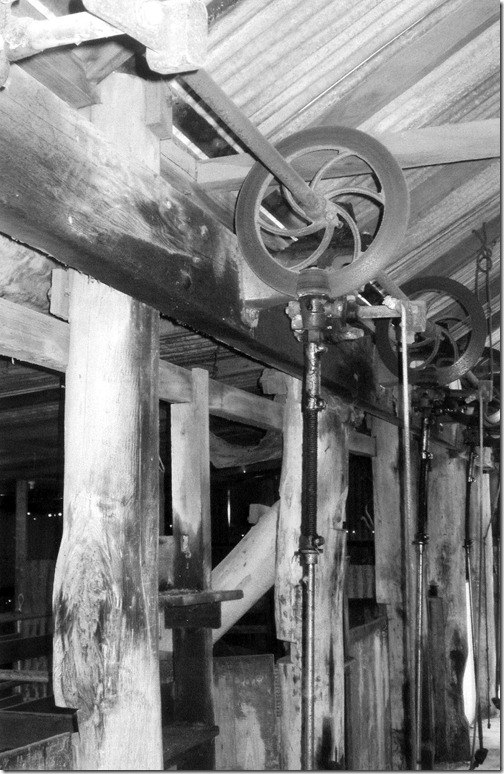

Original Woolshed

Current Woolshed (extended in late 90’s)

The original livestock were Herefords and Merinos. Market demands and trends have meant a third of the herd remains as a Hereford base, a third is aimed at the Angus premium market and the remaining third aimed at the crossbred market, where high growth rates can be obtained through hybrid vigour. Australian beef is part of the worlds’ highest quality meat, known for its consistency and being safe and disease-free.

In 1964, while already having a Merino flock, the first ewes were purchased from the Fulloons, which are now the sort after ‘Cressbrook’ bloodlines. Fine merino wool and mutton production is still an important part of the production on the property. In the mid – late ‘70s, fat lamb production was introduced, however, their feed requirements were found to be too high for return and they were phased out in the early 1990’s. Wool continues to play an important role and is somewhat iconic on the New England tablelands.

Over the years, improved pasture management has led to a much higher yields and efficiency per hectare. Originally we grew permanent pastures of cocksfoot, fescues, ryegrass and clovers. These days, a high-performance short-term pasture is sown down which includes high performance ryegrasses and herb species such as plantain, chicory and clover to provide finishing feed for fattening cattle, before establishing a high performance permanent pasture.

Improved Pasture

Fertiliser usage on the property has also come a long way over the last century. In the early days, single super was a major investment, with large returns. Currently however, although still important, fertilising the country has moved along with the advancements of soil and pasture testing. The addition of lime and natural products/by-products of other industries, such as chook manure have proven to be worthwhile both in a sustainable, environmental sense and also in regard to return in improved growth of pasture. We have now adapted and are developing the country through means of biological farming; introducing ‘good-bugs’ back into the country.

Surviving three droughts over this time stands testament to those who were looking after it at the time. Future dry times are sure to return cyclically but with the use of sustainable agriculture, increased knowledge and better management practices we are confident we will be resilient.

Like many Australian farmers our family are dedicated to undertaking weed control, pest and disease management and habitat and biodiversity enhancement.

We are testing both our soils and our pastures and creating nutrient maps so we can pinpoint exactly what the soil needs in order to remain ‘fuelled-up’ to continue being sustainably productive.

We have fenced of our waterways and have dedicated areas put aside to increase biodiversity and provide safe habitats for native flora and fauna.

Growing up a Grills…

With such a large extended family and great community spirit, growing up here was something I’ll cherish forever. I have four sisters, three of which are married with 7 kids between them. Horses were a massive part of my childhood and provided many a great time, which still continues today.

Starting early – 12 months old with my Dad

I grew up with them, not ever remembering even how I learnt to ride. My father was a keen and talented campdrafter, whilst us kids competed in ribbon days, and attended pony camp and travelled to shows all around.

Pony Club in 1995

We moved back into the Polocrosse scene when I was about 10, and haven’t looked back since.

Steph says catch me if you can

Cattle and sheep work was simply just a way of life. Very rarely were there ‘days off’, as there was always something that needed to be done or checked. There are many great memories growing up mustering cattle or being lucky and being ‘let into’ the big shearing shed when we were just tiny. From heading out at dusk with Dad, probably when I was meant to be having a bath and getting ready for dinner and bed, to check on a heifer calving, or to go down to give a poddy one last pat goodnight.

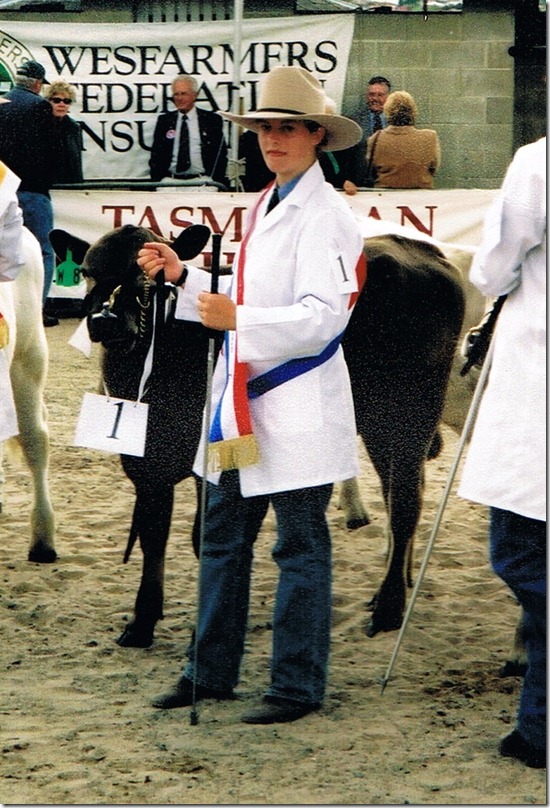

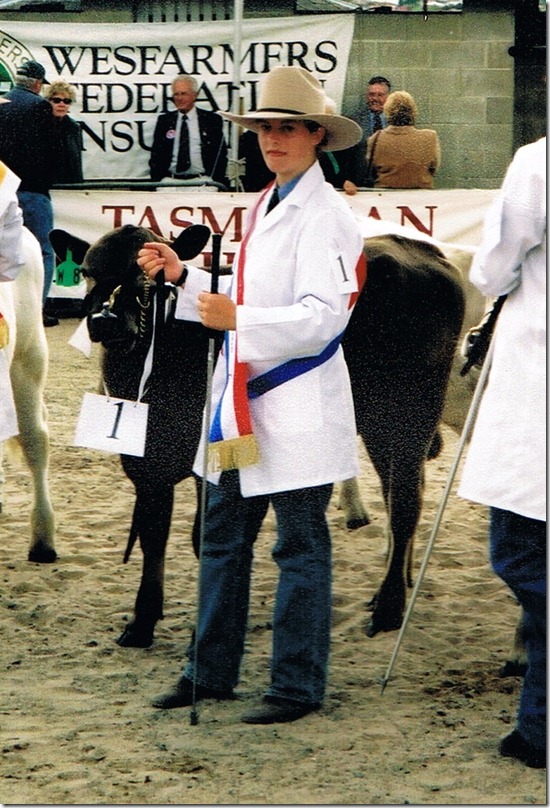

It’s a passion instilled as a youngster that I wouldn’t change for quids. I went off to boarding school at 11 years old and counted the hours when I would get to go home of a weekend. The school cattle team brought me some reprieve and ‘filled the gap’ a little. It was here that I had the opportunity to go on and win the National title for Beef Cattle Parader at the Hobart Show in 2002.

Winning at Hobart Royal 2002

It wasn’t until my final two years of school where I was able to study Agriculture and Biology, that I really found school somewhat enjoyable. So I threw myself into my studies, especially for these two units, and came out the other end of my HSC, with the award for Agriculture, Hospitality and a merit award for Biology. I was accepted early into University through the School/College Recommendation Admission Scheme. However, university wasn’t at the top of my list. I went home to work for twelve months on the farm and decided that I needed some qualifications to back me up. I completed my Certificate IV in Agriculture through a traineeship program at home. But from here I wasn’t sure what to do. I knew I wanted to follow on with Agriculture and I loved the livestock industry, so I enrolled at UNE, to study my Bachelor of Livestock Science.

Although different paths have taken me away from completing this until now, I have learnt a lot in the past few years and have made some wonderful friends across the country.

I even moved to Mungindi, NSW for 2 ½ years to become the offsider in a broadacre spraying operation. Although my family had had cattle on agistment around Moree and I had grown up with a few friends out that way, I knew very little about the cropping industry and its a time which I will cherish both for the knowledge learnt and the great friendships gained.

Mungindi Cropping

The future of Australian Agriculture…

I believe the future for Australian agriculture will be very bright. So many people are now voicing their support for Australia’s food and fibre producers, from all different walks of lifes and as a farmer this is so rewarding to see. No longer are farmers and all those working in the industry, just sitting on the fence, just like me they are starting to share their stories with the community. I am excited to be part of an innovative industry that is leading the world in technology and adapting it on a practical level. I’m very proud to say that Agriculture has been passed down over nine known generations and spans over three centuries just in my family. My hope is that this continues, and that the future generations can be just as proud as I am that they grow world class food and fibre. I also hope by sharing my story I can inspire other young people to follow me into an agricultural career

“Life on The Land – Don’t ever give up!”

1. WOOLCOMBER ( Taken from Family Tree magazine November 1996 Vol 13 no 1)

Woolcombing was part of the process of worsted manufacture. In the manufacture of woollen textiles the raw wool was carded to lay the tangled fibres into roughly parallel strands so that they could be more easily drawn out for spinning. Wool used for worsted cloth required more thorough treatment for not only had the fibres to be laid parallel to each other but unwanted short staple wool also had to be removed. This process was called combing. It was an apprenticed trade, a seven year apprenticeship being the norm in the mid 18th century with apprenticeship starting at about the age of 12 or 13.

The comb, which was like a short handled rake, had several rows of long teeth, or broitches – originally made of wood, later of metal. The broitches were heated in a charcoal fuelled comb-pot as heated combs softened the lanolin and the extra oil used which made the process easier. The wool comber would take a tress of wool, sprinkle it with oil and massage this well into the wool. He then attached a heated comb to a post or wooden framework, threw the wool over the teeth and drew it through them repeatedly, leaving a few straight strands of wool upon the comb each time. When the comb had collected all the wool the comber would place it back into the comb-pot with the wool hanging down outside to keep warm. A second hank of wool was heated in the same way. When both combs were full of the heated wool (about four ounces) the comber would sit on a low stool with a comb in each hand and comb one tress of wool into the other by inserting the teeth of one comb into the wool stuck in the other, repeating the process until the fibres were laid parallel. To complete the process the combed wool was formed into slivers, several slivers making a top, which weighed exactly a pound. The noils or noyles ( short fibres left after combing) were unsuitable for the worsted trade so were sold to manufacturers of baize or coarse cloth.